|

| Desert landscape in Tilcara, Argentina. |

|

| Me at Teotihuacan in Mexico in September 2018. Only one week into the trip, I had no idea if or when I would make it to Bolivia. |

|

| Making new friends at a hostel in Santiago, Chile. |

|

| Another new friend, Agostina (Agos), in Salta, Argentina. |

In addition to the visa fee of $160 USD, you must present a visa application form with a 4cm x 4cm color photograph, a passport valid until the date of departure from Bolivian territory, evidence of a hotel reservation or a letter of invitation in Spanish, round trip ticket or copy of itinerary, proof of economic solvency (credit card, cash, or a current bank statement), and an International Vaccination Certificate for yellow fever.

I also read several blog posts from other travelers who had crossed the border at the same location without having a visa in advance. The most recent and most helpful post had similar information regarding what the author had to do to get her visa.

My hostel in Tilcara did not have a working printer so, after filling out the online visa application, creating a hypothetical itinerary, booking a hostel for my first few nights in Bolivia, and downloading a recent bank statement; I then converted all of those documents to PDFs and uploaded them to Google Drive. I also took photos of my passport and vaccination card and uploaded them to my Drive. Then I went to the local internet cafe, logged into one of their very old computers, and downloaded the documents to the hard drive so they could print them. Unfortunately, they did not have a color printer, and I soon discovered that in the tiny town of Tilcara there was only one shop which had a color copier. The girl told me she could make photocopies of my passport and vaccination card but that the copier was out of toner and more was arriving by bus (yes, that's how everything is transported in much of Central and South America) that afternoon. A few hours later I finally had all of the necessary documents in hand for a total cost of $2.12.

|

| I had already walked into town and had a few hours to wait for the toner to arrive, so I revisited Tilcara's church which was all dressed up for Semana Santa. |

|

| La Albahaca was a great hostel with a friendly vibe, including a delicious communal dinner on my last night in Tilcara. |

|

| Approaching the border between Argentina and Bolivia. |

|

| This is the bridge at the border between La Quiaca, Argentina and Villazon, Bolivia. |

|

| This is one block from the border on the Bolivian side. The vendors have put up sheets and blankets to protect their wares from the afternoon sun. |

The agents said I could leave my bags in the immigration office while I went in search of more cash. They also kept my passport. I took my day bag containing all of my debit and credit cards, cash, etc. and started walking up the street into the town of Villazon, Bolivia. There were tons of "cambios" on both sides of the street as well as shops and vendors selling just about everything you could possibly want. I went into a few of the exchange places to check the rates (I still had some Argentinean pesos that I wanted to convert to Bolivianos) and to ask if I could trade my $20 and $10 bills for $100's. The answer was the same everywhere, "no." I quickly realized I would need to find an ATM to get enough Bolivianos to pay the visa fee. The nearest one was four blocks uphill farther into town. Thankfully, it worked with no problem, and I withdrew enough money for the visa plus enough cash to get to Tupiza.

|

| The view of the border from the Bolivian side. |

When I returned to the immigration office a crowd had gathered on the bridge at the border crossing. A few members of the local press were there as well. Everyone was watching a group of school children along with several adults and a handful of musicians. They were all dressed in red and were either wearing or carrying large bags and boxes of food items like rice, flour, and potatoes. As I walked up they started dancing and marching at the same time. Even the immigration office staff and armed border patrol guards came out to watch. They told me it was a protest relating to the taxes or fees for transporting goods across the border. I honestly have no idea why children were involved but I suspect it has something to do with education or welfare. They danced their way back and forth along the Bolivian side of the border for about 15 minutes, then we all went back inside the office to process my visa.

|

| The protesters. |

I ended up paying 1,100 Bolivianos (approximately $156) for a 10-year multiple entry visa. Once they had put the visa into my passport and attached a copy to my folder, it was filed away in a large cabinet. The same woman took me back across the border into Argentina and gave my passport to the agent there so I could officially be stamped out of the country. Then she gave me my passport and said "It's finished now." We walked together back into Bolivia and I retrieved my luggage from the immigration office. I thanked the woman for being so patient and friendly (we even did the typical Latin American greeting of a kiss on the cheek) and we said our goodbyes. The total time from start to finish, including the currency exchange and trip to the ATM, was one hour. It would have taken less than 15 minutes if I had the "correct" cash.

|

| Woohoo, I'm legal! |

I then walked back uphill about six blocks to the rapidito terminal to catch a ride to Tupiza. I had to wait about 20 minutes until the next minivan filled up before we could leave, but since I was one of the first people to arrive, I got to sit in the front passenger seat. This turned out to be a good choice because they ended up squeezing a total of nine adults (including the driver) and two infants into the small van. Plus the road between Villazon and Tupiza was pretty curvy on the second half and I imagine I would have felt motion sick if I was sitting in the back. Two hours later I was settling in to my single room for the next three nights and feeling quite proud of surviving the border crossing. Keep in mind that I did all of this in Spanish and at an altitude of over 11,000 ft!

|

| My ride from Villazon to Tupiza, Bolivia. |

One final note on the reason why I didn't go back into Chile. I already knew from my travels in March that Chile was definitely more expensive than Argentina. I had done my research on San Pedro de Atacama and knew that I was going to spend an average of $75 per day on lodging, food, and tours into the desert. Even the bus ticket to San Pedro was almost $40, compared to a total of $10 to go from Tilcara to Tupiza by bus and rapidito. I would also still have to pay for a bus and/or tour from San Pedro to Uyuni, Bolivia, a minimum of $30 for the bus and around $200 for a 3-day tour of the desert and salt flat.

|

| The places circled in red are where I will overnight on my tour (going clockwise). |

Instead, I came directly to Tupiza and from here, tomorrow, I will depart on a 4-day/3-night tour all the way to Uyuni. I will still get to see the Bolivian side of the Atacama Desert plus similar geological features like geysers, hot springs, lunar landscapes, lakes filled with flamingos, an active volcano, and finally the famous salt flat. My daily cost here is less than $20 and the all-inclusive tour costs $200. Thus I will spend less the half of the money I would have spent getting to San Pedro, touring the desert, getting to Uyuni, and touring the salt flat. And when I went to the tour office to prepay for my tour yesterday, I was able to get rid of all of those "worthless" $20 and $10 dollar bills!

|

| Catedral de Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria in Tupiza, Bolivia. |

So in the end it all worked out, which I was totally confident about the entire time but probably caused myself some unnecessary stress by not preparing everything for the visa further in advance. I continue to be thankful for so many things including all the friendly and helpful people I've met on this trip, my overall health and well-being, and the amazing scenery and culture of Central and South America.

|

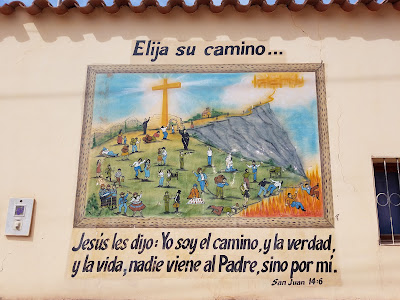

| Wall mural in Tilcara, Argentina. |

Happy Easter!